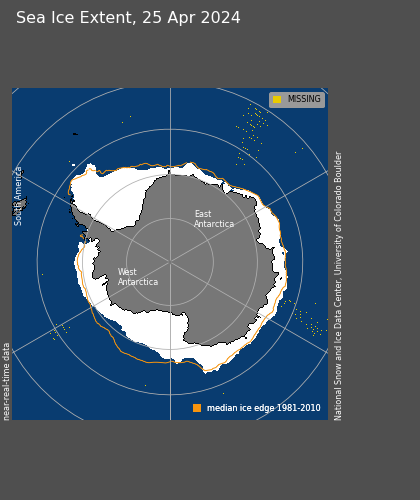

Le ultime due previsioni (ottobre 2008 e gennaio 2009) elaborate da David H. Hathaway del NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, che riducono l'ampiezza del ciclo 24: il massimo scende al di sotto di quello del ciclo 23 (fonte:

Stefano Di Battista: 11-01-2009 ore 21:02

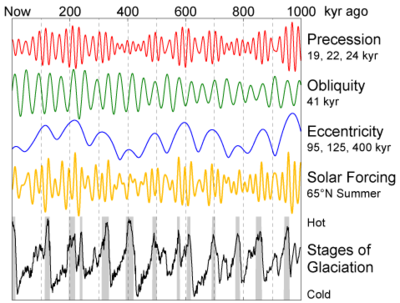

I sostenitori del riscaldamento globale antropico hanno una posizione perentoria: «Tutte le teorie che hanno cercato di attribuire alla radiazione solare un ruolo determinante sull'andamento delle temperature nell'ultimo secolo e, in particolare degli ultimi 50 anni, non reggono» [Caserini, p. 103]. Eppure ci sono studi che mostrano come la componente solare spieghi il 74% dell'evoluzione termica dell'emisfero boreale dal 1610 al 1800 e il 56% di quella successiva, e pur avvertendo che solo un terzo degli 0,36 °C di aumento registrati dal 1970 sono attribuibili alla variabilità solare, concludono che essa «può aver giocato un ruolo più grande nel recente mutamento di temperature globali di quello che finora è stato riconosciuto» [Lean, p. 3198].

Il filo che lega Sole e clima terrestre sembra correlato ad alcune componenti che possono amplificarne, oppure limitarne, gli effetti. Nella sintesi seguente si descrivono quelle su cui, al momento, si concentrano le maggiori attenzioni.

Fasi solari Il ciclo delle macchie ha una periodicità di 11,2 anni (ciclo di Schwabe); si tratta d'un dato medio, poiché sono documentati cicli di 9 anni e altri di 14. Il passaggio da un ciclo all'altro è determinato dall'inversione della polarità delle macchie, il che implica che ogni 22 anni circa (ciclo di Hale) il campo magnetico del Sole torni allo stato iniziale. La durata dei cicli di Schwabe è correlata al ciclo di Gleissberg, di 80-90 anni: ogni fase alternerebbe cicli lunghi, in cui il Sole si mostra meno dinamico, e cicli corti, in cui l'attività magnetica s'intensifica. A supporto di tale ipotesi si fa notare come i cicli 16-22 (si esclude il 23 poiché ancora non esiste certezza circa il suo esaurimento) abbiano avuto una durata media di 10,4 anni e un basso numero di Spotless days, mentre i cicli 10-15 (1856-1923), quelli cioè per cui risulta più certo il conteggio delle macchie (la compilazione storica regolare ebbe inizio nel 1849, durante il ciclo 9), siano durati in media 11,3 anni e con un più alto numero di Spotless days (*),

Eruzioni vulcaniche Un grande capitolo, su cui esiste accordo pressoché unanime nel mondo scientifico, è quello dell'influenza sul clima delle polveri vulcaniche immesse nella stratosfera. Il Dust veil index (DVI) è stato elaborato per misurarne la concentrazione. Se si scorrono le tavole cronologiche di tale indice, si noterà come il minimo di Dalton sia coinciso con una forte attività vulcanica: fra il 1799 e il 1822 (cicli 5 e 6) ci furono non meno di 12 eruzioni [Lamb, pp. 434-435], tra cui quella del Cotopaxi (Ecuador) nel 1803 (DVI = 1.100 circa) e quella del Tambora (Indonesia) nel 1815 (DVI = 3.000). Il XIX secolo e l'inizio del XX furono caratterizzati da un'altissima attività vulcanica (**), ma poi subentrò una stasi e «poiché le eruzioni vulcaniche hanno segnato un minimo marcato tra il 1912 e il 1948, tale situazione ha certamente favorito il sensibile aumento della temperatura verificatosi in quel periodo» [Pinna, p. 174].

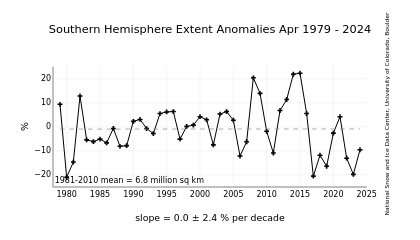

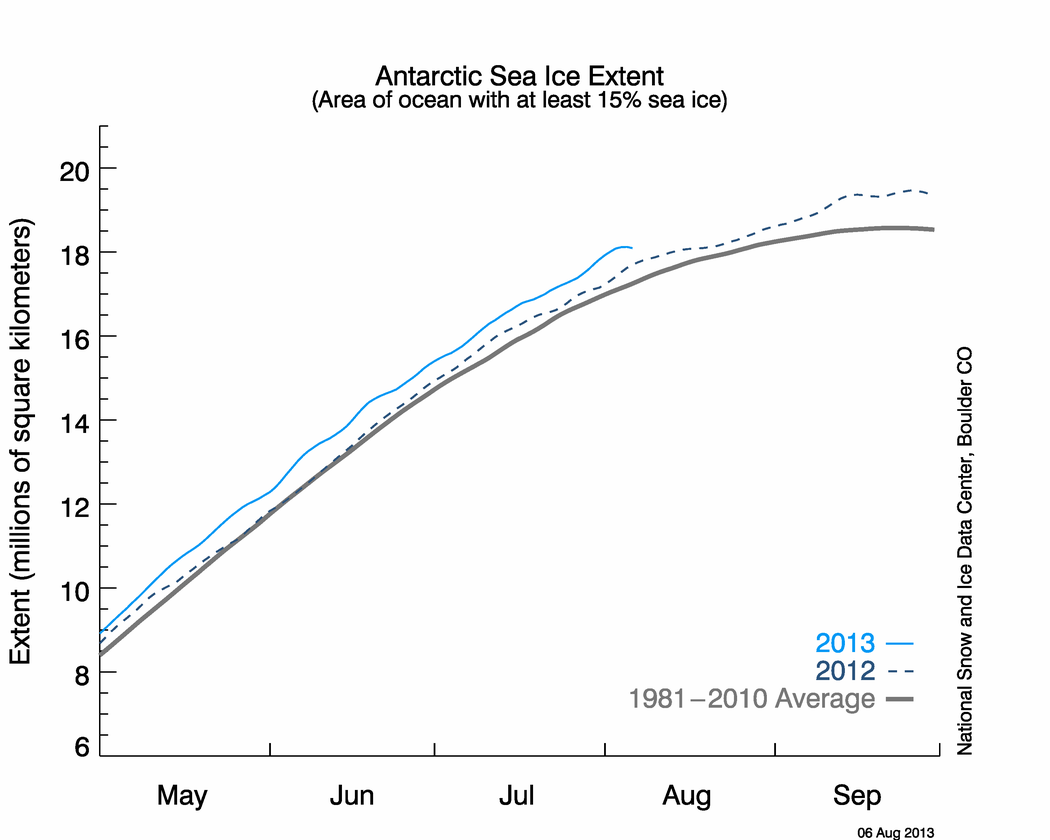

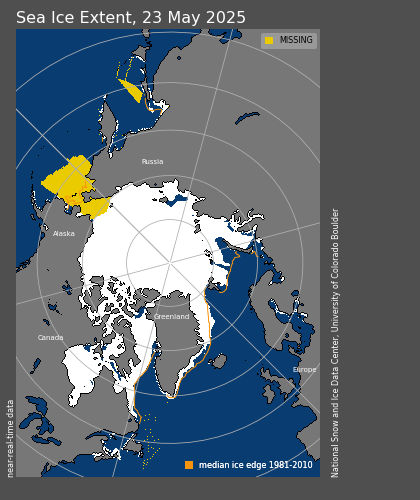

Teleconnesioni Si ritiene che, durante le fasi di forte attività magnetica del Sole, ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) sia preponderante rispetto alla Niña e viceversa. A partire dal 1976, in coincidenza coi cicli 22 e 23, ENSO avrebbe avuto un non trascurabile impatto sulle variazioni climatiche. Stando al ciclo di Gleissberg, nei prossimi anni è attesa una prevalenza della Niña, con conseguente moderazione degli eccessi climatici notati a cavallo del XXI secolo. Anche la PDO (Pacific Decadal Oscillation) e la NAO (North Atlantic Oscillation) sembrano correlate al ciclo solare, ed entrambe starebbero entrando in una fase negativa (fase fredda), che andrebbe a sommarsi alla debolezza di ENSO, amplificando gli effetti d'un minimo solare sul quadro termico terrestre. Si è poi tentato di mettere in relazione al ciclo undecennale anche la QBO (Quasi-Biennal Oscillation), ma con risultati di difficile valutazione.

Questo insieme di elementi potrebbe spiegare, almeno in parte, il riscaldamento dell'ultimo secolo e fornire indicazioni probabilistiche sulla futura evoluzione del clima terrestre. In questo campo di studi, mettendo in relazione l'indice geomagnetico del Sole e lo Zürich Sunspot Number (ovvero il conteggio delle macchie), si è scoperto che esiste una forte somiglianza (di segno inverso, però) fra il minimo di Maunder (1645-1723) e il grande massimo solare del XX secolo. Nel 1923 infatti (inizio del ciclo 16), si evidenzia una brusca variazione nell'ampiezza e nella durata della curva di lungo periodo che descrive l'attività solare; essa raggiunge l'apice intorno al 1960, poi comincia a decrescere [Duhau, pp. 8-9 e 14], in una parabola che dovrebbe riportarla al punto zero proprio con l'inizio del ciclo 24.

Ciò che, a oggi, si può affermare, è che il ciclo 23 è stato più lungo dei precedenti ma caratterizzato da meno macchie solari. Quanto al ciclo 24, le proiezioni elaborate negli scorsi anni lo descrivevano come il più forte degli ultimi secoli; la comparsa del nuovo massimo, invece, è stata via via posticipata e ridimensionata. David H. Hathaway, del Marshall Space Flight Center, considerato il maggior esperto mondiale in fatto di previsioni dell'attività solare, per tre volte ne ha riveduto l'ampiezza (Maximum sunspot number); ecco i dati che ha proposto:

145 (nel marzo 2006)

137 (nell'ottobre 2008)

104 (nel gennaio 2009)

Sorprendente l'ultima, forte correzione, ad appena tre mesi dalla precedente che, se confermata, condurrebbe a un debole ciclo 24 come non si verifica dal ciclo 16 (1923-'33). D'altro canto, la quiescenza del Sole nel 2007-'08 e in quest'inizio del 2009 è fonte di incertezze, che vanno a rafforzare la possibilità che il ciclo di Gleissberg conduca a un accentuato minimo verso il 2030: cosa questa che, combinandosi con le fasi negative delle principali teleconnessioni, potrebbe determinare un progressivo raffreddamento del clima terrestre, in antitesi a quanto postulato dalla teoria del riscaldamento globale antropico. Una possibilità, si è detto, che trova fondamento in una ciclicità abbastanza chiara dell'attività solare, la cui componente magnetica resta tuttavia un sistema caotico e non lineare, sull'evoluzione della quale è bene esercitare cautela: altrimenti si rischia quella che è stata definita ciclomania [Le Roy Ladurie, p. 13], che pretenderebbe di descrivere il clima futuro con estrapolazioni statistiche molto lontane dalla realtà dei fatti.

Note

Questa corrispondenza è resa dal grafico pubblicato a corredo dell'articolo http://www.meteogiornale.it/news/read.php?id=19367.

* Si è anche ipotizzato che l'intensità del vento solare, influenzando le linee di flusso del campo magnetico terrestre, possa modulare l'attività vulcanica; si tratta però d'una supposizione rimasta finora a livello accademico.

Bibliografia

S. CASERINI, A qualcuno piace caldo, Milano, 2008.

S. DUHAU, C. DE JAGER, The Solar Dynamo and Its Phase Transitions during the Last Millennium, in «Solar Physics», vol. 250, n. 1 (2008), pp. 1-15 (doi: 10.1007/s11207-008-9212-x).

H.H. LAMB, Climate: Present, Past and Future, vol. I, Londra, 1972.

J. LEAN, J. BEER, R. BRADLEY, Reconstruction of solar irradiance since 1610: Implications for climate change, in «Geophysical Research Letters», vol. 22, n. 23 (1995), pp. 3195-3198.

E. LE ROY LADURIE, Tempo di festa, tempo di carestia, Torino, 1982.

M. PINNA, Le variazioni del clima, Milano, 1996.

Parte I: http://www.meteogiornale.it/news/read.php?id=19372